Youth Agencies Adapt to Meet Pandemic-Era Needs

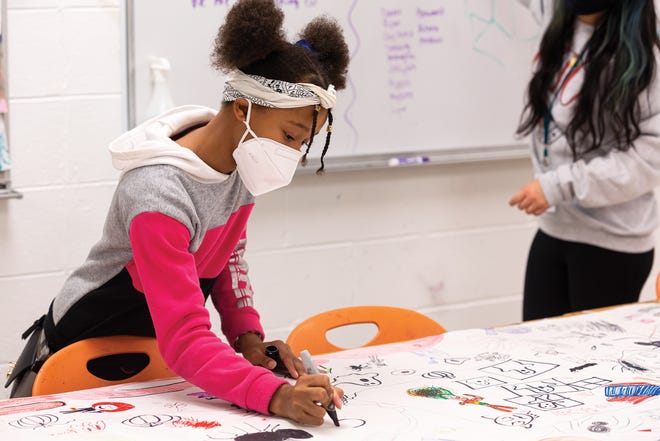

As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, agencies serving youth must continually adapt to changing needs.

Perhaps no single group in Central Ohio was more quickly affected by the coronavirus pandemic, or has been slower to return to pre-pandemic norms, than children.

It’s been a year and a half since Gov. Mike DeWine announced that school-age children throughout the state were dismissed from in-person classes, but the fallout is still being felt. In addition to the challenges of learning outside the classroom, young people whose parents lost employment had to live with their families’ struggles, pandemic-related or otherwise, day in and day out.

Vickie Thompson-Sandy, the president and CEO of Buckeye Ranch, says during the pandemic, Central Ohio saw increases in youth and domestic violence and emergency room visits due to a mental health crisis. Pandemic-related stressors exacerbated problems that already existed, from hunger to homelessness.

And without in-person classes, children lost opportunities to communicate concerns about their situation or well-being to teachers or other school-based helpers.

“Children … are in a developmental state where isolation is really not what they thrive on,” says Thompson-Sandy, whose organization serves young people with mental health, behavioral or other needs. “We also clearly saw our children feeling the stressors that their parents were taking on: unemployment, transitioning to working from home, trying to meet the needs of their kids when they had multiple children at home [and] limited income,” Thompson-Sandy says.

“The kids and families we serve had many challenges previous to the pandemic,” says Duane Casares, CEO of Directions for Youth and Families, a mental health agency that offers counseling and treatment programs to young people who have experienced trauma. But during the pandemic, “They really suffered more.”

Although there are reasons for optimism this fall, with most school-age children back in classrooms and the recent approval for vaccination against COVID-19 for children ages 5 to 11, the resumption of in-person learning still feels clouded by uncertainty.

“Kids need predictability,” says Thompson-Sandy, “and I don’t think we’re at that place yet.”

Even as they stress the need for in-person counseling and services, Central Ohio youth agencies have adopted virtual tools to address needs that were pressing before the pandemic, were made worse in the throes of the crisis, and are likely to linger for some time to come.

Directions For Youth & Families: From Telehealth to Pool Noodles

Founded: 1899

Annual budget: $7.8 million (2019)

Services: Counseling and treatment for young people experiencing trauma

In the early days of the pandemic, Directions for Youth & Families went from an entirely in-person organization to one that offered its counseling services almost exclusively via telehealth. But, just as many educators found virtual learning unsatisfactory, CEO Duane Casares discovered that telehealth had its own limitations.

“[Children] were being asked to do things for schoolwork on a computer, and then we have to ask them after that to be involved in a counseling center on a computer,” Casares says. “This really got old quickly. … Some parents were able to help; some parents weren’t. There were challenges of connectivity, or whether [families] had the data plans.”

Casares, who concluded that telehealth was generally more effective with adults than with children, began getting feedback from his outreach workers as early as June 2020 that they needed to see kids in person to know how they were doing. For instance, as staff conducted telehealth sessions with kids, they couldn’t always know who else was present in the room.

“They actually said to me, ‘You don’t seem to understand: Some of our kids are not in very healthy situations. We have to get back out and see them. We have to make sure they’re OK,’” Casares recalls.

In response, the agency implemented a pandemic-era pilot program in which six workers were sent back into kids’ homes, adhering to health and safety protocols in what was then a pre-vaccine world. “I think that we bought every pool noodle in the city that was available, because little kids don’t understand what 6 feet of social distancing is,” Casares says. “We did things like say: ‘You must meet them outside. You have to take your own chair. You have to have a pool noodle. Everybody must wear a mask.’”

Soon, the pilot program of six workers grew to 30. “Our frontline workers are just some of the most compassionate, caring, supportive and smart people out there,” Casares says.

Meanwhile, Directions’ after-school centers on the East Side—normally the site of everything from math, science and reading programs to arts education, including dance, singing and a steel drum band—were reimagined, for the first time in the agency’s history, as food distribution centers that also provided diapers, cleaning supplies and other products.

“That’s one of the ways we had to change to support the people that

we serve,” Casares says. “When families can’t get out to stores, and when people are infected, it’s not like they have a bunch of [products] sitting in their basement or attic. This is something that we truly had to get out to them.”

This fall, Casares says that most of Directions’ staff has returned to the field, but numbers at the agency’s after-school centers are still down, and the resumption of its in-school programs varies from building to building, depending on local COVID policies. But the need is as high as ever.

“I have a lot of friends who are schoolteachers, and some of them in prominent school systems … and they were all telling me that these are the worst grades that they’ve ever had to hand out,’” Casares says. “Affluent areas struggled with this. Well, certainly, our kids did, too.”

Huckleberry House: Layers of stress

Founded: 1970

Annual budget: $4.6 million (2022)

Services: Offers shelter and transitional housing for youths and young adults experiencing homelessness

Huckleberry House executive director Sonya Thesing is accustomed to seeing an uptick in demand for the agency’s youth crisis program at the start of the school year. “Once school starts, usually, there’s stress at home, but there are teachers and guidance counselors and coaches who are seeing that and saying, ‘Let’s get you to Huck House,’” Thesing says.

But during the past two Septembers—and, indeed, the past two years—Thesing has seen lower-than-usual numbers of young people at its crisis center. “That’s really troubling for us, because we know that the problem is there,” says Thesing. But with the closure of schools and community organizations where young people would ordinarily hear about the agency, “The youth are not being recognized as having a need—and they’re not being directed to help.”

At the same time, COVID-19 made it more difficult for Huckleberry House staff to help kids in crisis. “A lot of it was saying to parents, ‘I know things are really rough right now, but if you bring your child into our shelter, they might not be able to leave for 14 days [due to quarantining],” Thesing says. The agency’s crisis shelter remained open for all who needed it, but staff placed an emphasis on resolving problems using virtual tools when possible, providing counseling via Zoom, FaceTime or the telephone.

Thesing says that those who have made it to Huckleberry House during the pandemic often have intense mental health needs. The isolation has weighed on young people, as have additional day-to-day burdens. For those who lack internet access, the closure of libraries or fast-food restaurants with free Wi-Fi was daunting, she says. She calls it “a piling-on of the stress.”

In addition to operating a crisis shelter for those between 12 and 17 who, for reasons ranging from abuse to a family eviction, feel they can no longer live at home, the organization offers transitional living units—some 114 apartments throughout Greater Columbus—for those between 18 and 24 who have experienced homelessness and are seeking a path to independent living.

The housing programs experienced high demand, in part due to increased capacity, and caseworkers found themselves struggling to adjust to socially distanced methods of care. For example, about half of those residing in the agency’s transitional apartments have children of their own, Thesing says, but in-person contact between those young mothers and caseworkers had to be limited early in the pandemic.

“That lack of human connection really stalled the progress that we were able to make with the youth who, we would hope at a certain point, would be doing things independently,” Thesing says. “The toughest thing for our staff was not being able to hold the babies and not being able to play with the toddlers up close. Sometimes a young mom just needs a break: ‘I’ve been holding this baby for 23 hours. I need someone to come in.’ ”

Other practical needs went unmet due to the demands of social distancing. “We couldn’t transport them to Morse Road to get their SNAP benefits, and we couldn’t drive them to get their state IDs that they needed to get jobs,” Thesing says.

Over time, Huckleberry House caseworkers resumed meeting with clients by using the same pandemic tools as the rest of us: masking, opening windows, keeping 6 feet apart. “Maybe you could sit in the kitchen and maybe you could have your client sit in their family room,” Thesing says.

Children's Hunger Alliance: Increased Food Insecurity

Founded: 1970

Annual budget: $14 million (2021)

Services: Provides meals to youths experiencing hunger via after-school, summer and other programs

In 2019, according to an analysis by the organization Feeding America, 1 in 7 children in America lived in a household that could be described as food-insecure—a rate that, while alarming, was the lowest in two decades, the organization said.

Yet those gains have been erased by the pandemic: Feeding America projects that in 2021, 1 in 6 children are likely to experience food insecurity. Judy Mobley, president and CEO of Children’s Hunger Alliance, says that the trend in Central Ohio is much the same.

“You’re always wanting to see improvement, and I think we would have said Ohio was making progress [before the pandemic],” says Mobley. “But, in light of what we’ve been through, there’re more kids than ever that need our help.”

Last year, Mobley faced the challenge of bringing food to schools that, after switching to remote learning, could no longer provide breakfasts and lunches to children. After-school programs, during which Children’s Hunger Alliance and similar organizations provided dinner meals, also ground to a halt.

With schools having returned to in-person learning this school year, breakfasts and lunches are again being served to young people in Central Ohio. “Honestly, we just sort of hold our breath in our work every day that schools stay in-person, because that makes a huge difference to hungry kids,” Mobley says. Yet after-school programs—which offer not only meals but valuable academic resources, such as homework help—are coming back more slowly.

“We probably don’t have as many after-school sites right now as we would have in a typical year, but that’s continuing to grow,” says Mobley, who also points to reticence on the part of parents who, even if they feel it’s best for their children to attend school during the day, are reluctant to potentially expose them to the virus in an after-school setting.

“[The parents] may just say, “Well, my kids have been staying home—do I really need the service anymore?’ ” Mobley says. “Our perspective is, the after-school sites provide so many positive things for kids that we would highly encourage people: If you have a need for care for your kids, an after-school site is a perfect location.”

Mobley remains concerned about getting Central Ohio kids fed during breaks in the school year or over the summer; thanks to the waiving of certain USDA rules, Children’s Hunger Alliance has maintained a robust network of mobile meal sites this summer and last. “Right now, we can go to a park and [say] we’re going to be there from 11 to 11:30,” Mobley says. “[The families] will be there, and we’ll hand them the meals, and then we’ll go to the next stop.”

But, she adds, “If those waivers don’t continue into next summer, then we will not be able to do as much mobile feeding.”

Buckeye Ranch: The Resilience of Youth

Founded: 1961

Annual budget: $49.4 million (2019)

Services: Residential treatment and outpatient programs for children with emotional, behavioral and mental-health needs

It’s been a year of disruption and opportunity at Buckeye Ranch, which, in addition to its residential treatment programs, also provides community and outpatient services for its clients.

At the organization’s Grove City campus, where 300 young people receive treatment each year, clients had to stay put when the pandemic hit. “We had to go into protecting them by keeping them on our campus,” says CEO Vickie Thompson-Sandy. “They did not go home to their families.”

Youth staying at the facility connected with their families virtually, but those sessions did not always alleviate their anxiety. “They heard and saw the stress that their family was going through,” Thompson-Sandy says. “That impacted them as well, as they heard about their parents losing their jobs and worrying about food stability.”

Also impacted were those young people who, as part of their course of treatment, had often been permitted to return home during the weekends; to help avoid spread of the virus, those visits stopped. “It was really, really difficult for them,” Thompson-Sandy says. “It’s just not the natural state for all of us to be confined.”

With the advent of vaccination and rapid testing and a better understanding of virus risk factors, young people staying on the campus are now going home on weekends, Thompson-Sandy says.

Yet the pivot to telehealth was beneficial for some families outside the residential setting, removing barriers they faced in using Buckeye Ranch’s services. “Families always experience difficulty with child care, they always experience difficulty with transportation, they always experience a difficulty with inflexibility of work schedules,” Thompson-Sandy says. “Telehealth removed that for a lot of families. Access to services increased for families.”

The pandemic has taught the longtime leader another lesson, too. “This is my 31st year in the field, and I always am amazed … at how resilient kids are,” she says. “I think that we will learn from that.”

This story is from the 2022 issue of Giving, a supplement of Columbus Monthly and Columbus CEO.